A pilgrimage of creativity

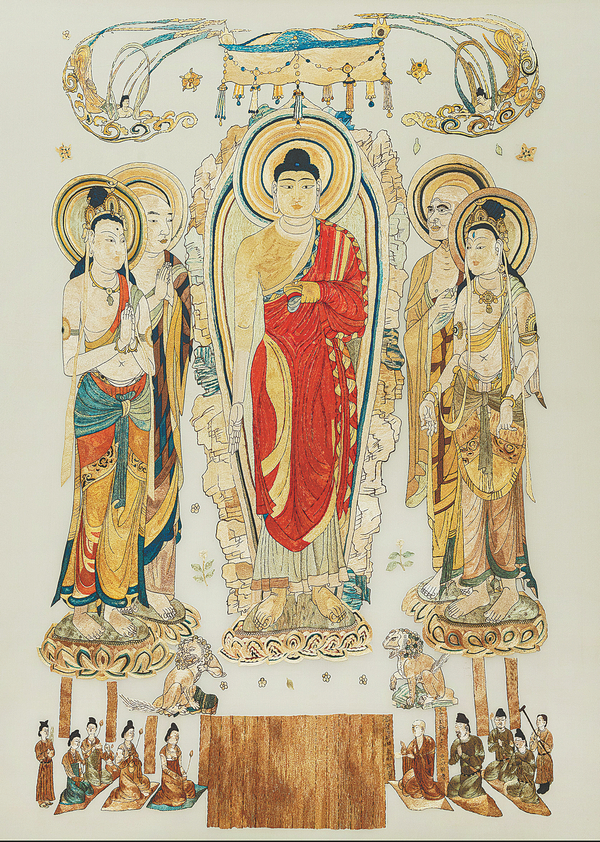

Zou Yingzi made a decision in 2015 that changed her life and, it could be said, enriched society. That was the year she discovered the story of the famous embroidery Miraculous Image of Liangzhou, which shows the Buddha preaching. The work, which dates back to the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties, is 2.4 meters high and 1.6 meters long and was stored and preserved in a cave with Buddhist scriptures at the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, Northwest China's Gansu province. In 1907, it was taken to Europe by Hungarian-British explorer Marc Aurel Stein, later becoming a part of the collection of the British Museum.

Zou, who is based in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, learned embroidery from the age of 6 and became a city-level inheritor of suxiu, or Su embroidery. She decided to embroider a copy of the ancient work, but the following years, living up to this commitment, were difficult and costly.

Actually seeing the work was a feat in itself, as its popularity meant that it was often displayed far from London. The artwork was loaned out by the British Museum to the Getty Research Institute in the United States in 2016 and the Nara National Museum in Japan in 2018.

Undeterred, Zou requested the details, such as its actual size, from the repair room of the British Museum, read volumes of relevant literature, consulted experts, and dismantled her own work six times before her final offering was warmly praised by experts. She then donated the work to Dunhuang Academy in 2019.

Zou's Su embroidery works are being shown during Suzhou Arts and Culture Week highlighting the culture of Suzhou in Beijing from Thursday to Jan 20. The event is part of the 22nd Meet in Beijing International Arts Festival, which kicked off on Thursday and runs until Feb 18.

The festival, with an aim to celebrate the upcoming Beijing Winter Olympics and Winter Paralympics, includes a series of cultural and artistic activities like a grand gala, dramas, exhibitions and dances.

Famous for its history and culture, Suzhou was admitted to the UNESCO Creative Cities Network as a capital of crafts and folk arts in 2014. The city has six items that were each listed as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. It has many intangible cultural heritage items, including Kunqu Opera, K'o-ssu (Kesi), a traditional type of decorative silk work in China, and guqin (a traditional musical instrument).

As a style of Chinese embroidery, Su embroidery is crafted in areas around Suzhou, and is famous for its meticulous and varied stitching, elegant colors and beautiful patterns. The works Zou brings to Beijing include a wedding dress, perfume satchels and other items showing the culture of Jiangnan (regions south of the Yangtze River) and various techniques of Su embroidery.

Zou showcases the pattern of a lion placing its paw on an embroidered ball that she is showing at the exhibition. This is an auspicious image in China. "In traditional Chinese culture, this pattern often appears as a celebration for festivals or big events, so I want to show it to celebrate the upcoming Olympics," says Zou.

Innovation has been a close companion and, in a very real sense, she is re-creating the craft. She holds several patents for new embroidery techniques she has developed or rediscovered. One in particular is noteworthy. When she embroidered the Dunhuang work, she recovered a technique called "split stitch", which was used in the creation of the original tapestry, but had long been lost. She then made another embroidery piece using the technique and donated it to the National Museum of China.

Another highlight of the arts and culture week is a set of fans made by Wang Jian, also a Suzhou native, a provincial-level inheritor of intangible cultural heritage. Historical literature shows that the craft of fan making developed in the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), and the accessory became very popular among the literati during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Men of letters considered fans a status symbol.

Wang agrees that fan making-involving making the frame and covering and carving it-is an intricate art.

"A craftsman usually perfects only one craft, since it is too difficult for one person to master all. For example, making the cover contains three major steps, and one needs to learn each for about three years," Wang says. "Moreover, one must put their whole heart into one craft. I learned how to make fans over the course of 20 years, and I mainly work on making the frame and designing the covering now, requiring others to help me complete the fan."

He started learning the craft at the age of 16, when he worked at a factory making fans in 1981. He gets inspiration wherever he goes. He recalls that once he went to a beach, and collected shells and made them a part of a fan.

A standout example of his work at the exhibition is a fan made with an ebony handle and golden paint in a style that was popular during the Ming Dynasty, but the manufacturing techniques it required had been lost in the mists of time.

In 2006, Wang wanted to see if he could master the necessary skills to make the fan. "I noticed some fans, as cultural relics unearthed from tombs, show a technique different from what I have learned, so I wanted to have a go and see if I could resurrect the technique," says Wang.

He sifted through pages upon pages of literature, and borrowed a fan from a collector. After much trial and error he finally mastered the technique.

In an era of mass production, Wang insists on making handmade artworks, and makes about 10 fans a year. "I insist on making every one of my works in a unique fashion, so it is difficult to make many. Moreover, good materials are not easy to find. So I would rather make a few quality fans than make many that are inferior."

Wang hopes the exhibition will reignite interest in his chosen craft. "Through this opportunity, I hope more people will pay attention to traditional crafts like fan making. Many people may have never seen our fans before, but by visiting the exhibition they will get to know the different types of fan, and the elegance of ancient ways."

Contact the writer at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn